As for today's topic, these are not necessarily my favorite guitarists, or a comprehensive list of the ones I think are the best. I'll get to that, don't worry. No, these five I'm honoring here are the ones I believe have had the most influence on the instrument, the way it's played, the way it's presented, and the prominence it now enjoys. Last time I saw a figure on the subject, it was estimated that there are roughly 20 million guitar players in the United States. We have just emerged from what could easily be called "The Century of the Guitar." If that is true, all twenty million of us should bend the knee to these five people.

And, no, these are not exhaustive biographies or discographies of these people. For that, I recommend you start with http://www.allmusic.com/.

The first on the list (which is roughly chronological, by the way) would have to be Andres Segovia. He was born in Spain at a time when the guitar was something that proper ladies learned to play so they could entertain guests in the parlor. I'm sure you've seen instruments that were referred to as "parlor guitars." Well, that's what they mean. It's one of the things you learned at charm school.

Oh, yes, there was guitar music, and even professional guitarists, but it was considered a small instrument that played small music. It was Segovia that forced the world of music to acknowledge it as a serious musical instrument. He showed it to be a versatile instrument rhythmically, harmonically, and melodically. He transcribed many great works for the guitar, and commissioned many more. By the time he reached middle age, composers were lining up to write for the guitar, and for Segovia.

Once he'd established its potential, Segovia fought long and hard to maintain the purity of the classical guitar. To the end of his performing career he refused any form of amplification. To his ear, even a microphone could not accurately reproduce the tones. A Segovia concert, no matter the size of the hall, was absolutely silent while the Maestro played so that nobody would miss anything. In middle age he met a young Chet Atkins. He was quite taken with the talented young man, and even gave him playing tips, until he found out that Atkins played electric guitar. He never spoke to him again.

In spite of this, he was a prolific recorder and a shameless promoter, not only of his own music, but of the classical guitar in total. And just as shameless an innovater. Just about everything that we take for granted about the classical guitar, from the little footstool to the length of scale, the shape of the body, the construction, the tuning, just about everything was directly influenced by Segovia.

To put it simply, the guitar as we know it - not just classical guitar, but the guitar in total as a musical force - would not exist without Andres Segovia.

The next on the list is Charlie Christian. He has been called "The first guitar hero." As big band jazz was giving birth to be-bop, he proved that the recently-invented electric guitar could solo right along with the trumpets, saxophones, etc. Until Charlie, the guitar was relegated to the rhythm section along with the drums and upright bass. Comp chords and keep time. It didn't matter if you could play scales and runs, because nobody could hear you over the horns anyway.

Jazz guitars were arch-topped in order to help them project, and builders tried everything they could think of to make them loud enough to keep up with the band. When Gibson began producing the ES (for Electric Spanish) 150 Charlie was one of the first pros to get one. Before long his name became synonymous with that model. It also became synonymous with jazz guitar. When musician's musician Benny Goodman put together a sextet on the side, he tapped Christian to play guitar. The Benny Goodman Sextet not only laid the groundwork for the next twenty years of jazz innovation, it was the first major multi-racial band in American popular music.

Unfortunately, Charlie Christian died in 1942 at way too young an age. As I recall, it was tuberculosis that claimed him. Whatever it was, he was only in his twenties. To me, that makes it even more amazing that he had such a huge influence in such a short time. Every time you hear an electric guitarist take a solo, thank Charlie Christian.

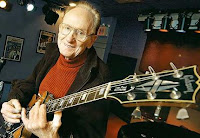

Which brings us to Les Paul. If Les had never played a note, he'd have been a huge influence on modern music. The man invented multi-track recording, fer cryin' out loud! Before Les Paul, you went into a studio, turned on the machine, and hoped you could produce a good performance. If you wanted something to be heard on your recording, you'd better bring it with you.

Les figured out that if you put two recording heads side by side, they could record two different tracks on the same piece of tape. Before long he and his wife, Mary Ford, were making recordings in their home using nothing but his guitar and her voice. Amazing recordings, rich in tone, timbre, and harmony. On the road, they didn't need a band. Just a copy of the backing tape. Throughout the late '40's and early '50's they produced hit after hit.

Les was also an innovator of guitar construction. He had the idea for a solid-body electric years before anybody was making them. He tried for years to get Gibson to listen to him. They refused, until Leo Fender's Telecaster came out. Then, all of a sudden, it seemed like a pretty good idea after all. To this day, a Gibson Les Paul model is one of the most coveted guitars.

But after all that, you've got to sit down and listen to the man play. And damn, could he play! Still does, in fact. At this writing, he just turned 92. He still has a gig every Monday night at a club in New York City, and everybody who's anybody drops by to listen, and maybe even jam a little. Les had - and has - that wonderful combination of technique and flash that makes his music irresistable.

Next up; Chet Atkins. Quite simply, this man has influenced the playing of practically everybody who's followed him. What is most surprising about that is that he did not come from the world of Classical music, or even Jazz, but Country-Western. Classical, and nowadays Jazz, get studied in college. Country, on the other hand, is now and has always been a music of the people. In spite of this, or maybe because of it, Chet has without a doubt influenced more guitarists than anyone who ever lived.

Quite simply, this man has influenced the playing of practically everybody who's followed him. What is most surprising about that is that he did not come from the world of Classical music, or even Jazz, but Country-Western. Classical, and nowadays Jazz, get studied in college. Country, on the other hand, is now and has always been a music of the people. In spite of this, or maybe because of it, Chet has without a doubt influenced more guitarists than anyone who ever lived.

A brief history of fingerstyle country guitar goes sort of like this; in the beginning was Mother Maybelle. "Can The Circle Be Unbroken" is only one of the many famous songs Maybelle Carter wrote for the Carter Family. In the '20's and '30's, she, husband A. P. Carter, and her siblings - and later, her daughters - would harmonize, often accompanied by nothing more than Maybelle's guitar.

She had a unique style for the day. She would play a melody on the bass strings with her thumb, and in counterpoint strum chords on the upper strings with her fingers. It was a simple style that created a lot of music. The great Merle Travis turned the idea on its head by playing alternating bass notes with his thumbs and countering with arpeggios and melodies on the treble strings with his fingers.

These two greats by no means invented fingerstyle guitar, however. It was the standard way to play Classical guitar and lute, long before Segovia came along. But most Jazz, Country, and other "folk" musicians strummed with a plectrum. Mother Maybelle and Merle helped bring a new level of harmonic and rhythmic sophistication to their music.

Enter one Chester Atkins. As a young man he was hungry to improve his playing, and so he began studying Classical guitar. And yet, instead of becoming a Classical guitarist, he brought what he learned back to the music he loved. This as much as anything about Chet proved to be a huge influence on all who followed him. Nowadays it's common for musicians to cross the lines between styles. In Chet's day, it was considered a pretty radical thing to do.

Chet went on to become A&R Chief for RCA records, as well as the label's senior producer. In this role he literally set the standards for country music for decades. He is the man we can thank - or blame - for bringing country music uptown. He is the reason that the best musicians and songwriters can now be found in Nashville.

Toward the end of his life as he began to step away from the business end he returned to his first love; the guitar. He recorded a number of duet albums with musicians he admired, including Merle Travis, Mark Knopfler, and two grammy-winning collaborations with Les Paul. He was practically a regular on the Prairie Home Companion radio show.

The final guitarist on my list is none other than James Marshall Hendrix. Like Charlie Christian, his life and career were cut short. And, like Charlie Christian, he forever changed the way that guitarists approach their instrument.

The final guitarist on my list is none other than James Marshall Hendrix. Like Charlie Christian, his life and career were cut short. And, like Charlie Christian, he forever changed the way that guitarists approach their instrument.

No comments:

Post a Comment